A world title, then a final, then another world title between 1994 and 2002. On the surface, it looked like a golden age for one of soccer’s giants, Brazil. Packed with stars, carrying an aura that felt almost untouchable, and feared for their attacking firepower, this team had names that still resonate today: Ronaldo, Rivaldo, Roberto Carlos, Cafu, and a young Ronaldinho beginning to shine. But behind the façade of dominance, between the 1998 and 2002 World Cups, Brazil went through years of turbulence. Frequent coaching changes, injuries to key players, and underwhelming performances raised doubts. Few remember it now, but Brazil came dangerously close to missing the 2002 World Cup altogether. How did the Selecão go from 1998 finalists to struggling in qualifiers? And why was their fifth world title such a massive surprise ?

- A soulless Brazil in World cup qualifiers

The qualifying campaign was long and exhausting for a disastrous Brazil. Inconsistent to the extreme, capable of both strong performances like a 6-0 victory in Venezuela and massive collapses away from home defeats in Uruguay, in Argentina, and especially in Bolivia during the penultimate match that left the Seleção in a dangerous position. Why such a drop in level at the start of the Asian World Cup qualifiers? After all, it was surprising for a team that had been a finalist in France ’98 and had won Copa América 1999 in style. Could those recent positive results have been nothing more than illusions, hiding deep flaws within Brazilian soccer ? The explanation for Brazil’s collapse at that time can be summed up in one name: Ronaldo Luís Nazário de Lima. Brazil is a land of stars, where several great players can coexist in the same XI. But Ronaldo was the one everyone agreed on. Considered the best player in the world and feared in 1998, the 1997 Ballon d’Or winner was struck down in mid-flight on November 21, 1999, during an Inter Milan Serie A match against Lecce. He tore his patellar tendon and was forced into five months of recovery until April 2000. On April 12, 2000, in a decisive Inter match against Lazio at the Stadio Olimpico, Ronaldo seemed to glimpse light at the end of the tunnel with his first appearance after five months… but tragedy struck. He collapsed again, this time suffering a complete traumatic rupture of the same right patellar tendon. The Brazilian champion now faced a very long recovery that would sideline him from late 1999 until the 2001-2002 season. Nearly a year and a half without football—for a Brazil that mourned the absence of its superstar.

Ronaldo was the UFO of Brazilian soccer: a unique player, an indestructible aura. In Brazil, the team naturally played for Ronaldo. He was the star. All the cracks soon came to light, especially the inconsistency of other attacking players such as Rivaldo, Romário, and Ronaldinho, each trying to step into the superstar role in Ronaldo’s absence. Ronaldo missed all the qualifiers, and his absence revealed deeper problems that were surrounding Brazilian football. Two stood out: the instability of the Brazilian federation and a failing development system. Corruption weighed heavily on Brazilian soccer, with scandals costing several leaders their positions including coach Vanderlei Luxemburgo. Between involvement in shady transfers, falsifying his age, and accusations of tax fraud, the coach embodied a federation riddled with sickness at the top. The scandal was so severe that the Brazilian Senate even created an inquiry commission to shed light on irregular transfers, such as Dida’s. Youth development was another problem. In major cities, kids increasingly played only in paid academies. A selection based on money excluded countless talents. Journalist Geraldo Couto of Folha explained: “Urbanization processes wiped out the vacant lots where kids once tried their first dribbles. A child trained in a club or soccer school has less chance of being creative.” He added another layer of critique about the loss of Brazilian authenticity: “There is a standardization of world football where physical and tactical preparation has taken precedence over individual talent. By losing, at least partly, the brilliant spontaneity of its athletes, Brazilian soccer has had to adapt to modern times. It has imported tactics, concepts, strengthened physical prep and discipline.” Loss of spontaneity, instability within the federation, and instability on the bench: Brazil went through four coaches between 1998 and 2002. Luxemburgo, fired after his scandals; interim coach Candinho; and the short-lived Emerson Leão, who arrived after the disastrous 2001 Copa América (eliminated by Honduras). By the end, it was Luiz Felipe Scolari who had to finish the qualifiers with Brazil in flames. After a 5-0 debut win over modest Panama, Brazil lost in Argentina and Bolivia, leaving them on the brink. The final match against Venezuela was now do-or-die: victory or risk an intercontinental playoff against Australia. On November 14, 2001, Brazil defeated Venezuela 3-0 and ended a catastrophic qualifying campaign, finishing third far behind an Argentina side that looked terrifying.

- Romario vs Ronaldo : which star to trust

After such a grueling qualification, Brazil was heading into the unknown before the Asian World Cup. Which XI to field, with so many strikers tested but none truly convincing: Romário, Edílson, França, Euller, and also the “Europeans” Mário Jardel, Sonny Anderson, Giovane Élber, and Márcio Amoroso. Which system to play? What were the objectives? Countless questions flooded the Brazilian press, which reveled in stirring up debates around a Seleção shrouded in uncertainty. Coach Luiz Felipe Scolari had only one idea in mind for his World Cup: Ronaldo. Scolari swore by Il Fenomeno’s presence and assured him he would be “the centerpiece” of his system during a visit to the striker in April 2001. Scolari fought against all odds to back his star R9. Against Ronaldo’s club, Inter Milan, which wanted to take no risks. Against coach Héctor Cúper, who refused to change his methods for Ronaldo’s fragile fitness. After returning on September 20, 2001, following 18 months without football, Ronaldo suffered several minor muscular injuries caused by inactivity and Cúper’s extreme caution, which denied him the rhythm he desperately needed.

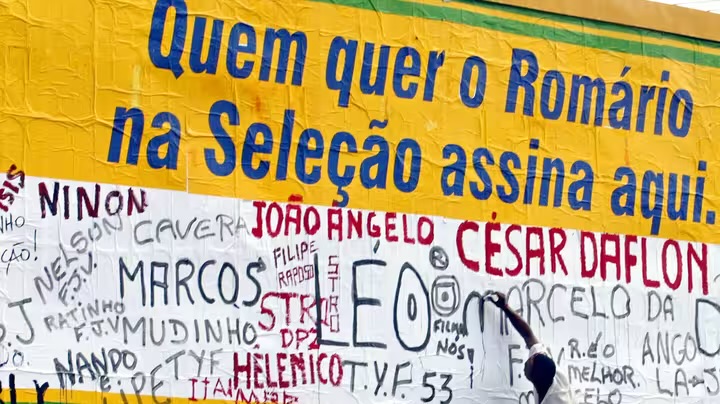

Meanwhile, Brazilian fans clamored for Romário, in superb form with Vasco da Gama. An absolute idol, Romário was an eccentric whose brilliance and personality made him irresistible. He could even call Pelé a “moron” without losing popularity. Loved or hated, Romário never left anyone indifferent. As his form at Vasco was compared with Ronaldo’s struggles at Inter, public opinion overwhelmingly favored him for the World Cup squad.

Internally, Scolari remained inflexible. No matter Romário’s form, no matter Ronaldo’s limited game time in Milan, no matter his minor injuries or poor showing against Portugal, the coach was unwavering. For him, only Ronaldo could restore order in the team, tame egos, and create collective spirit. The Ronaldo vs. Romário saga perfectly illustrated what Scolari brought to Brazil: serenity. Ronaldo survived thanks to his coach’s faith, who built a family-like environment. Scolari wanted no players who would disrupt discipline—and given Romário’s baggage at the time, coexistence would have been impossible. It was in this family cocoon, built around the comeback of Ronaldo, that Brazil entered the 2002 World Cup.

- A chaotic World cup journey

At the start of the 2002 World Cup, Brazil was far from favorite. The struggles of qualification had been underreported outside Brazil, and attention focused on other giants. France, fresh off their 1998 and Euro 2000 titles, had Zidane at his peak showcased by his Champions League final goal for Real Madrid—along with Henry, Cissé, and Trezeguet, each top scorer in their leagues. Argentina, with Marcelo Bielsa’s guidance and an exceptional qualifying campaign, were also tipped. Then there were Germany, England with its golden generation, Italy’s Euro 2000 finalists and their ferocious defense, and Portugal led by Ballon d’Or winner Luís Figo. Brazil, on paper, looked more like an outsider. Goalkeeper Marcos was solid but not elite. Lucio, Roque Júnior, and Edmílson were young and untested internationally. Gilberto Silva, Juninho Paulista and Ronaldinho also offered limited big-stage experience. And then there was the great unknown: Ronaldo. Only Rivaldo, Roberto Carlos, and Cafu stood as guarantees, with their age, stature, and experience. In a group with Turkey, Costa Rica, and China, Brazil were favorites, expected to cruise and build momentum. But the opening match against Turkey was a wake-up call. The Turks played fearlessly, rewarded just before halftime when Hasan Şaş scored on a pass from Bastürk. They knew Brazil’s defense was shaky and carved open chances on the counter. That’s when Ronaldo showed why Scolari had fought so hard for him: he equalized with an extended finish. Brazil only prevailed late, aided by the controversial expulsion of Alpay (after a Rivaldo dive) and a penalty that should never have been given (the foul was outside the box). Pushed to the brink, Brazil needed an undeserved red card and penalty to edge Turkey. The next matches against China (4-0) and Costa Rica (5-2) were handled better, but the opposition was too weak to provide real lessons.

The lack of certainties came back in the Round of 16 against Belgium. The Red Devils had only qualified at the last minute, so Brazil underestimated them. Roberto Carlos even mocked on Brazilian TV that Belgium was “the most dangerous team of the tournament.” With no pressure, Belgium unleashed themselves. Mbo Mpenza gave Roberto Carlos nightmares, Marcos made crucial saves to keep Brazil alive, and the Seleção were rattled. Then came the moment of shock: Marc Wilmots rose above Roque Júnior and scored with a header. It seemed a logical reward for Belgium’s dominance—but the goal was controversially disallowed for a slight push. Belgium had missed their chance. Thirty-five minutes of doubt haunted Brazil, before individual brilliance once again saved them: Rivaldo and Ronaldo scored to crush Belgian dreams. Victory was secured, but doubts persisted.

Next up was England hardly a reassuring opponent. The Three Lions impressed, led by a vengeful David Beckham after his 1998 red card, with Ferdinand, Scholes, Campbell, and Ballon d’Or holder Michael Owen. But on June 21 at Shizuoka’s Ecopa Stadium, Brazil displayed their full class. Wearing blue, they dazzled with technique and flair none more so than Ronaldinho. He slalomed through the defense to set up Rivaldo’s equalizer, then scored a legendary free kick from long range. Even after being controversially sent off, Ronaldinho had already tilted the match. Brazil, playing with bold attacking football, controlled the game. England were powerless. What was expected to be a tight contest became a Brazilian showcase. With this win, Brazil suddenly looked like the team destined to win the tournament. In the semifinal, they faced Turkey again. Ronaldo made headlines before kickoff with his bizarre haircut, designed to divert attention from his injury concerns. Playing at only 60% of his capacity, he scored the decisive goal with the tip of his boot—the only part of his leg that didn’t hurt. Brazil were one step from history: a fifth star. But Germany awaited.

Germany, led by Oliver Kahn, was feared for its defensive strength and near-impenetrable wall in goal. Before the final, individual awards were handed out, and Kahn was named Player of the Tournament. With six goals already, Ronaldo could have claimed that honor, and the final became a personal duel for redemption. Revenge for the 3-0 defeat to France in 1998, and proof that he was indeed the best player of the 2002 World Cup. As destiny would have it, Ronaldo scored both goals in Yokohama. The first came after Kahn spilled a Rivaldo shot; the second finished Germany off. Brazil won 2-0. Ronaldo, written off two years earlier, had risen again.

After a chaotic path littered with obstacles, instability, injuries, structural issues, Brazil 2002 concluded in the best possible way: lifting their fifth World Cup. That triumph was, above all, a surprise. A nation on the brink of collapse found salvation in the family forged by Luiz Felipe Scolari. By escaping the hysteria of public pressure, Brazil rediscovered unity and glory.